I count myself as being truly fortunate in being granted the opportunity of placing Rhodesian Ridgeback pups in South Africa’s Kruger National Park, the KNP.

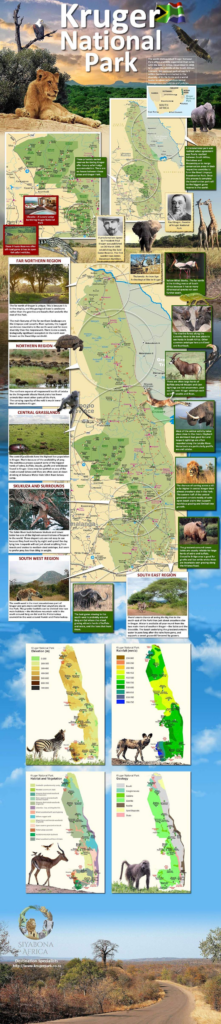

That Park, bigger than several countries, is about 500 kilometres from top to bottom. It represents the last bastion of an unaltered natural environ

Changing weather patterns have caused drought conditions to develop in much of the center of the Park, and desertification brings a new challenge to the wild animals, many of whom must face up to the never ending fight for survival. But our Ridgeback is not a prey animal there, though many of the smaller ungulates act with great caution in their presence, and even the mighty Elephant decides that he must approach them with care. This is the environment for which or dogs were designed, and this is the place where they can employ the skills and physical attributes with which they are so richly endowed. But the name of the game in this, the KNP world, is survival. Nature requires two simple rules for life there, and the first is survival. After that the second is a bit easier, but equally important; it is the need to procreate.

The Section Rangers in the KNP, of whom there are 22, are permitted under their contract of employment, to be accompanied on the job by their dogs. This is a particularly sensible approach. When you are concentrating on this or that problem you may not be as aware of what is going on around you as circumstances demand. That Rhodesian Ridgeback at your side is exquisitely aware of every move made by the dangerous ones which happen to be directly around both the human and himself. And he does not trust one of them. In fact he looks scathingly at his human when he barges in and breaks the most basic tenets of survival. But he also understands that the two of them are a team, and that if the chips are down they fall together. At no time has a Ridgeback deserted his human. Should your regular dog leave the protective shield of his human, say he escapes out the gate and goes on an adventure, it is estimated that his remaining lifespan has just reduced to 30 minutes. This is regardless of how healthy he was; his state of health has little bearing on his survivability. We have yet to lose a Ridgeback in this fashion, but then they don’t leave their home turf unless instructed to do so. But we did have to learn that a dumb dog is a dead dog and how to look at the training issue. Requirements as to the physical qualities of the dogs could not have been more minimal.

Scotty Stewart (ZA)

I was born at the foot of Lion’s Head, Cape Town, South Africa, in 1936. Within the year we moved to London as war clouds gathered over Europe. In 1939 I was sent to Bo’ness in Scotland to live with my mother’s parents, while she and my father were sent to serve in India. At the age of eight I was given a Grey Scottish Terrier, and my association with dogs began. He was quite a shocking little beast, and I regularly collected him from the police station, to which he had been taken by well-meaning people.

In 1948 I returned to South Africa, via Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia. From there I flew to Johannesburg, to be reunited with my parents after a break of nine years. I had not been back in South Africa for a week when I learnt all that anyone needed to know about the Rhodesian Ridgeback. They were very popular dogs then; every second household seemed to have one. We were spending the day at my uncle’s home on the outskirts of the city. A group of us went for a walk, taking the Gooderham dog Topsy behind us. We were very soon going to be extremely glad we had done so. We were strolling slowly through the tall grass when Topsy rushed past us and leaped into the grass ahead.

She had grabbed a very long Rinkhals, or Spitting Cobra. She seized it in her jaws, and shook it violently, not giving it the slightest chance to strike at her. She was picking it up randomly along its length, shaking it violently in her jaws, and then releasing it. I am sure that the first time she shook it it’s spine snapped, but I suppose that she continued just to make sure that it was harmless. If she had not been so alert some one would probably have stood on it with dire consequences; snakebite treatment was not all that successful seventy years ago. In 1954 we moved into a house 15 km from the centre of Johannesburg. It was a very basic life.

We generated our own electricity, and pumped our own water. Chickens, goats, sheep and cattle roamed freely, and there were no tarred roads, no roads at all really. We discovered very quickly why most people had Ridgebacks; it was because they were resistant to biliary (much the same as Tick Bite Fever in humans) which could kill a dog within hours. In 1963 Anneliese, the girl next door (literally) and I married, and had two daughters and a son.

The girls were both avid horsewomen, and in the 1980s, we bought some farmland to accommodate a growing herd of ponies and horses. Fortunately our elder daughter, Helen, who was twelve at the time, contacted Laurie Venter of Glenaholm fame, and arranged to acquire a Ridgeback bitch. She was called Pippa by us, and Rockridge Lady Anne by her breeder, ‘Smiler’ Howard. We were now irretrievably linked to Ridgebacks. Our eldest daughter was to involve us yet again, many years later, in what proved to be the most fascinating world the Ridgeback can enter, and it gave me personally the greatest possible enjoyment, reward, and enrichment. She was contacted by a Section Game Ranger, Ralf Kalwa, who was stationed at Malelane in the Kruger National Park, and we were able to place the first registered Rhodesian Ridgeback in one of the few places left on the planet where the breed that was designed for it could once more walk with lion in the very same environment in which Cornelius Van Rooyen had created it more than a century earlier. Ralf was the beginning, and his Dusty was followed by another dozen examples of the breed. They all served their humans with dedication, but I was soon to discover the secret of what permitted these dogs not only to enjoy, but to survive, the exacting nature of raw Africa and its most powerful and deadly predators, et al. It did not matter how healthy they were, how well balanced, well angulated, the correct colour, etc. etc. What they could not survive without was actually very obvious. It was all just too simple, they had to have intelligence. They proved in a very short few months that in an environment as basic as the KNP, a dumb dog was indeed a dead dog. Humans proved it many years earlier. When everything comes down to survival, nothing beats intelligence.

Scotty is chairman of the board of the Rhodesian Ridgeback International Foundation

Papers presented at the RRWC (Rhodesian Ridgeback World congress) in Lund 2016